Redaction with local VLM and LLMs

Overview

Redaction workflows require both text and bounding box identification from documents. In this post, I will test local vision language models (VLMs) from the Qwen 3 VL family against existing OCR tools to see how well they can perform in identifying text and bounding boxes from ‘difficult’ documents. All the examples can be recreated on the Document Redaction app VLM space on Hugging Face. The code underlying this app can be found here.

OCR word-level text extraction vs ‘standard’ OCR

Many OCR tools exist to extract text from PDFs into formats such as markdown, and recent VLMs are extremely good at text extraction. However, for redacting personal information from documents, it is essential to have the exact page coordinates of every relevant word, as redaction boxes need to be placed on top of the words in their exact positions on the original document. Unlike more ‘traditional’ OCR solutions, most VLMs were not trained in returning line or word-level bounding boxes.

Existing OCR tools for word-level text extraction

For some time, local OCR models such as tesseract have existed for the purpose of identifying word text and position on the page for clean documents. Additionally, paid options have existed for more complex PDFs, such as AWS Textract. Both of these options can be tested in the live Document Redaction app space on Hugging Face.

These tools have limitations - the free tesseract model struggles to accurately identify text as soon as documents get noisy or complex. Other free OCR options such as PaddleOCR can identify line-level text positions, but do not natively support word-level coordinate extraction, and struggle with handwritten text. Paid options such as AWS Textract perform much better on handwriting, but the price can quickly rack up with thousands of pages to process. And even Textract struggles with scrawled handwriting and signatures.

New options - the Qwen 3 VL family

Despite recent advances in local VLM models, improvements in the redaction workflow space specifically have been lacking. Until recently, there has not been a low-cost way to extract text from complex documents, while identifying word-level coordinates. The Qwen VL family is one of the first local VLM models that has been trained to identify the position of text as well as its content (see here for examples).

With the advent of performant local VLMs (such as the Qwen 3 VL family), I thought it was a good time to try them out for testing the text extraction-redaction workflow. I imagine that a typical organisation would have many documents to process, and so would prefer smaller models would reduce cost and increase throughput. Local models also give the possibility of running sensitive documents on-system in secure environments. Finally, using small local models would give organisations the possibility of fine-tuning for specific document types to improve performance (this blog post is using the models ‘out of the box’, with quantisation to 4-bit).

NOTE: At the time of writing, the Qwen 3.5 VL family of models seemed to be imminent - I will reconduct all the tests in this post with the expected Qwen 3.5 VL 9B, and perhaps the 35B MOE model when they are released.

Why Qwen 3 VL 8B Instruct?

Qwen 3 VL 8B Instruct was chosen for this project as it is a small, fast model that is able to perform well on a range of tasks, including text extraction and redaction. It is also a good balance of performance and cost, as it is able to fit inside a reasonably-sized consumer GPU (16 GB VRAM) when quantised to 4-bit, which at the time of writing could be obtained for £400 (~$500) or less. Like the rest of the Qwen 3 VL family, it has been specifically trained to return line-level bounding boxes (see here), which in combination with the word-level segmentation functionality in the Redaction app, could make this model suitable for use within a redaction workflow.

All of the examples described below can be recreated on the Document redaction VLM space on Hugging Face. Visual outputs from each experiment are also provided below.

Example 1 - ‘Easy’ document OCR - where VLMs are not needed

Let’s start our investigation into local model OCR with a simple example - the first page of the document found here

We don’t need to use complicate solutions to extract text with word-level coordinates - often the simplest solution is the perfectly adequate. This is demonstrated at the Document Redaction VLM Hugging Face space, with the Baseline ‘easy’ document page example. As indicated by the name, this is a clear, simple document page without noise. Here we can see that current OCR solutions are adequate for text extraction, and the additional use of VLMs is not needed.

Click on the first example - ‘Baseline ’easy’ document page’, and click through the steps including the button ‘Redact document’. Then wait a couple of seconds for the results that appear in the output box.

‘Easy’ document OCR with tesseract

The default OCR option for this example is tesseract - a small, fast OCR model that has been many years in development. Below you can see the OCR output from the tesseract model. As you can see, it identifies the vast majority of the text with high confidence. The left page shows the pre-processed image with the identified bounding boxes overlaid. The right page shows the text identified by the model, with colour indicating the confidence of the analysis (green is high confidence, red is low confidence).

However, even with this ‘simple’ example, there are some issues. Tesseract extracts a few words with low confidence, and some are wrong. See ‘Connect globally - Thrive locally’ in the top left of the page. Can a more performant local model perform better? Let’s try PaddleOCR.

‘Easy’ document OCR with PaddleOCR

An alternative option to try is PaddleOCR, which uses a tiny VLM (pp-OCRV5), is quite fast, and performs much better than tesseract in general at the cost of speed and resource needs - details here. Another disadvantage particular to the redaction use case is that PaddleOCR (along with almost all open source OCR solutions) only identifies bounding boxes at the line level, not the word level. To account for this, the Redaction app uses post-OCR processing to segment line bounding boxes into word bounding boxes.

To test PaddleOCR with our baseline example, first click on the example at the Hugging Face space, but at step 2 (Choose text extraction (OCR) method), select ‘paddle’ instead of tesseract. Then run through the steps and click on ‘Redact document’ as before. Note that the Hugging Face spaces version of the Redaction app uses the CPU-powered version of PaddleOCR due to compatibility issues with torch and Spaces - the GPU-enabled version of PaddlePaddle run locally is much faster.

The results above are almost perfect - with the exception of an ‘I’ missed off INTERNATIONAL in the top left, and a misplaced bounding box cut in the top right with the first P of Partnership, caused by a relatively large gap in this title word that may have been created by page pre-processing techniques. Additionally, line to word level bounding box segmentation is still a method I am working on and could be improved - see here for the code.

Conclusion

Overall, I would say the performance on word-level OCR on this page is pretty similar between tesseract and PaddleOCR + post-OCR word segmentation. Personally, I would probably stick with tesseract for such ‘easy’ pages in documents without selectable text due to the speed increase. However, for anything more difficult that this tesseract clearly falls flat, as we will see in the following examples.

NOTE: as the page actually contains almost exclusively selectable text, even quicker text extraction with the pdfminer.six package can be used through the option ‘Local model - selectable text’. However, the purpose of this post is to compare OCR options, so from now on I will consider document pages with the assumption that some sort of OCR solution is needed.

Example 2 - Scanned, noisy document page

We’ll now try a more difficult page from the same document as above - page 6. This page is primarily a scanned document that contains significant noise, as well as signatures. We will test tesseract, PaddleOCR, and a hybrid PaddleOCR + Qwen 3 VL approach.

Scanned, noisy document page with tesseract

Click the second example name, ‘Scanned document page with signatures’, and on step 2 ‘Choose text extraction (OCR) method’, change the local OCR model option to ‘tesseract’. Then run through the other steps and click ‘Redact document’.

Below you can see the results of the OCR process:

As you can see from the above, the results are… pretty bad. The tesseract model seems to have become lost in the noisy text from the scanned document, frequently failing to identify individual words, and misreading the text completely. It has also missed the handwriting and signatures completely. I would say that tesseract is unusable for ‘noisy’ documents like these.

Scanned, noisy document page with PaddleOCR

As before, click the second example name, ‘Scanned document page with signatures’, and on step 2 ‘Choose text extraction (OCR) method’, change the local OCR model option to ‘paddle’. Then run through the other steps and click ‘Redact document’.

The results are as follows:

We can see that PaddleOCR performs much better than tesseract, but still has some issues. The bounding boxes for the lines are generally good, but at the word levelare not all accurate (which may be more due to to the word segmentation process). It has identified the handwriting and signatures, but the text identified is not always correct - see ‘Cit of Lona Beach’ near the top, ‘Sister Lity Agreement’ near the top as a couple of examples. The signature text detection is completely off. I would say that PaddleOCR is an ok option for ‘noisy’ documents with typed text, if you are not too worried about the accuracy of the handwriting or signature analysis.

Scanned, noisy document page with a hybrid PaddleOCR + Qwen 3 VL approach

We will now try a hybrid approach with PaddleOCR + Qwen 3 VL. In this approach, PaddleOCR is used to identify the bounding boxes for the lines, and then Qwen 3 VL 8B Instruct is used to re-analyse words that had low confidence from PaddleOCR. Additionally, a second VLM pass is conducted specifically to identify the position of signatures.

As before, click the second example name, ‘Scanned document page with signatures’, and on step 2 ‘Choose text extraction (OCR) method’, change the local OCR model option to ‘hybrid-paddle-vlm’. Then run through the other steps and click ‘Redact document’.

The results are as follows:

Words that the VLM had a try at re-analysing are shown in a grey box on the right hand side of the page. To do this, a small image is ‘cut’ from the original page image, and passed to the VLM to identify the text. Below is an example of one of these images from this page where the VLM has successfully corrected the phrase ‘Cit of Lona Beach’ to ‘City of Long Beach’:

Prompts underlying the above ‘hybrid’ approach (including the signature second pass) can be found here. The hybrid OCR function itself can be found here.

We can see that the hybrid PaddleOCR + Qwen 3 VL approach performs much better than PaddleOCR alone. It is however limited by the performance of the first PaddleOCR pass. As ‘Sister Lity Agreement’ from PaddleOCR was a high confidence analysis, the VLM did not have a chance to re-analyse it.

The signature text detection is slightly better, but still not perfect. The second pass VLM analysis correctly identified the positions of the signatures on the page, identified as [SIGNATURE] entries in the output (see the right hand page). In terms of reading text, the first signature is identified by the VLM as ‘Beperly O’Neill’ - almost perfect. The second signature is called ‘Dulus’ - which is incorrect, but a symptom of the fact that PaddlOCR identified only part of the signature as a valid bounding box for the word.

Scanned, noisy document page with Qwen 3 VL alone

Click the second example name, ‘Scanned document page with signatures’, and on step 2 ‘Choose text extraction (OCR) method’, change the local OCR model option to ‘vlm’. Then run through the other steps and click ‘Redact document’.

The results are as follows:

There are a number of issues with this analysis. First, the left hand side side of the page shows that frequently the bounding box locations identified by Qwen 3 VL are inaccurate - generally (but not consistently) to the right of where they should be (NOTE: don’t think this is a rescaling issue, as we will see for the example below that the bounding box coordinates are generally correct). Based on the results for this page, I wouldn’t recommend VLM analysis alone for this page with this model.

Conclusion

I would say that the hybrid approach is a good option for ‘noisy’ documents with typed text and mixed handwriting / signatures, if you are not interested in the specific text in the signatures. It is of course a slower and more resource-intensive approach than PaddleOCR alone, but the increased quality may be worth it, and it is still faster and more accurate than VLM analysis alone (33 seconds vs 84 seconds for analysis).

Example 3 - Unclear text on handwritten note

THere are of course many situations where it is important to accurately extract handwritten text from documents. This has long been a struggle for OCR tools, including paid options, but modern VLMs are getting better and better at this. How will a small model like Qwen 3 VL 8B Instruct perform? Let’s find out.

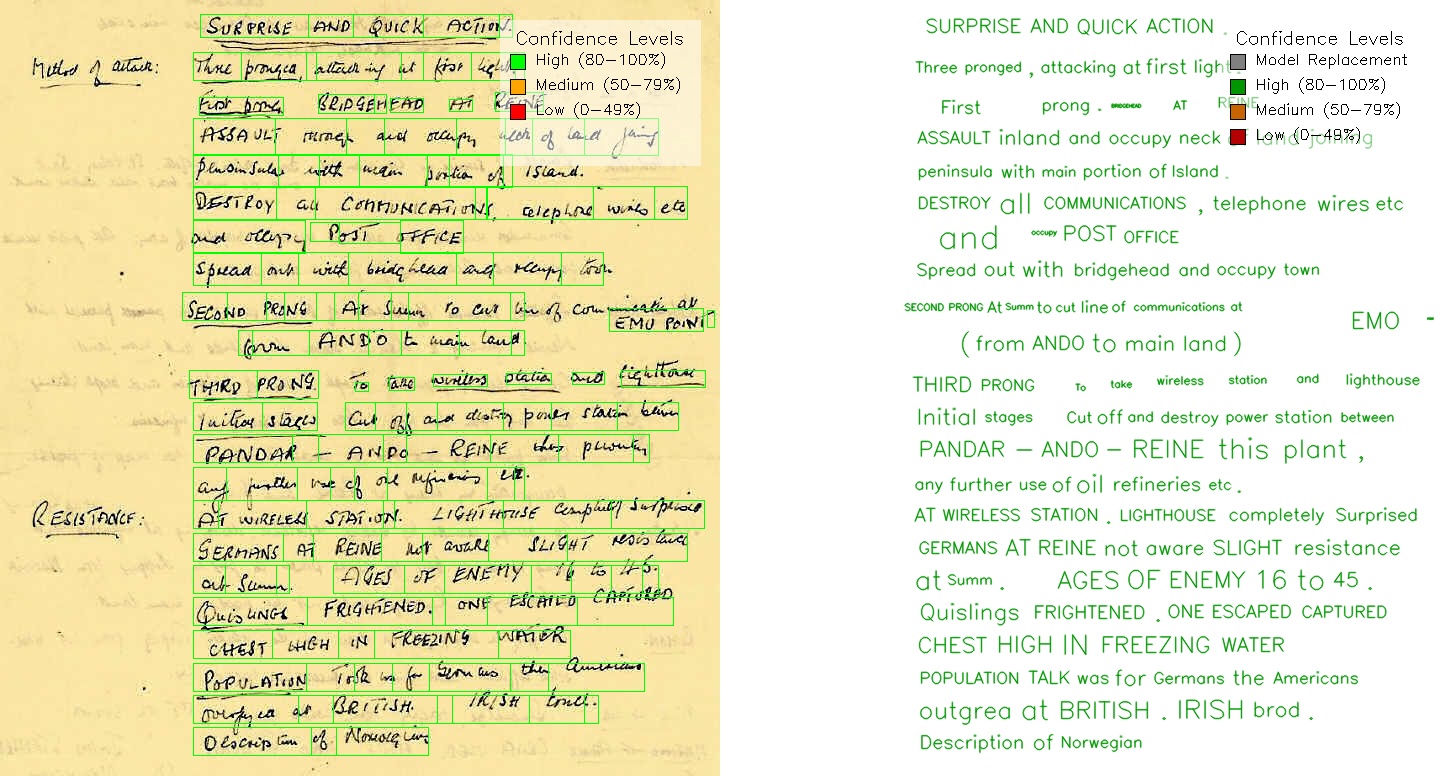

The document for this is example is below. As you can see, some of the text is very difficult for a person to read.

Let’s first use PaddleOCR as a baseline to compare with the pure VLM approach.

Unclear text on handwritten note with PaddleOCR

Click the third example name, ‘Unclear text on handwritten note’, and on step 2 ‘Choose text extraction (OCR) method’, change the local OCR model option to ‘paddle’. Then run through the other steps and click ‘Redact document’.

The results are quite poor. PaddleOCR has low confidence for the majority of the text, and the text identified is pretty consistently wrong, even in cases where the confidence was high. This shows once again that PaddleOCR is not a good option for handwritten text. At least in general the line-level bounding boxes are well positioned, so it may be worth trying again with the hybrid PaddleOCR + Qwen 3 VL approach.

Unclear text on handwritten note with a hybrid PaddleOCR + Qwen 3 VL 8B Instruct

_Click the third example name, ‘Unclear text on handwritten note’, and on step 2 ‘Choose text extraction (OCR) method’, change the local OCR model option to ‘hybrid-paddle-vlm’. Then run through the other steps and click ‘Redact document’.

This analysis is better. The text identified by the VLM is much more accurate, but still not great. The word-level bounding boxes are ok in general, but may be limited by the performance of the first PaddleOCR pass, and the line-level images passed to the VLM as part of the hybrid approach. A number of example line images passed to the VLM can be seen from the PNG files in this folder here.

I would say that this analysis is still not good enough. How could a pure VLM approach + word-level bounding box segmentation perform?

Unclear text on handwritten note with Qwen 3 VL 8B Instruct alone

Click the third example name, ‘Unclear text on handwritten note’, and on step 2 ‘Choose text extraction (OCR) method’, change the local OCR model option to ‘vlm’. Then run through the other steps and click ‘Redact document’.

The code for this approach can be found here.

The results in terms of text identification are better. The text identified by the VLM is generally accurate, with some exceptions (e.g. ‘PANDO - ANDO - REINE this plant’, which I think should be ‘PANDO - ANDO - REINE thus prevent’). I would say that this is pretty close to the level of accuracy that a human would achieve in transcribing from the same image.

Additional issues include that the analysis has completely missed a few words to the left of the page, an issue that I think could be model-specific, and a larger Qwen 3 VL model would likely perform better.

The bounding box locations at the line level are generally OK, and as before, word-level bounding box issues are more a symptom of the word segmentation process, rather than the VLM itself.

Conclusion

I would say that Paddle + VLM hybrid analysis is the best option for handwritten text. The text extraction quality may be slightly worse than the pure VLM approach, but I think the increased general reliability in terms of identifying line-level bounding boxes, and not missing text completely, puts it ahead for me.

I would also expect a bigger/more modern model in the Qwen VL family would perform better in text identification and bounding box location accuracy. Additionally, with the Qwen 3.5 series of small local models imminent, this conclusion may change very soon. I will update the analysis as soon as these models are available.

Example 4 - Bonus VLM features - face identification

The use of VLMs in the redaction process gives rise to some potential bonus features that are not possible with traditional OCR tools. Let’s see how the Qwen 3 VL 8B Instruct model performs at identifying faces in a document.

Choose the example ‘CV with photo - face identification’. The OCR method will be ‘hybrid-paddle-vlm’. Then run through the other steps and click ‘Redact document’.

The text on the page is relatively simple to analyse, and PaddleOCR performs well, with accurate text and bounding box locations. What’s of particular interest here is that we have prompted the second pass VLM analysis to identify photos of people’s faces in the document. You can see this in the top left of the page to the right, where the location of the applicant’s face is identified as [PERSON] in the output. The redacted PDF output shows this face blacked out here, with an Adobe Acrobat redaction commented version here (download it and open in a PDF viewer to see the comments added).

The prompt and response for the face identification can be found here. Of course, other visual features could be identified with the VLM with correct prompting.

Example 5 - Redaction with LLMs (Gemma 3 27B)

For identifying PII in redacted text, small language models have been used for some time, e.g. spaCy models perform relatively well throught the Microsoft Presidio package. Higher performance come from paid solutions such as AWS Comprehend. Both of these are also demonstrated at the Document Redaction app space. Both solutions lack contextual understanding of the text, and offer only a standard list of entity types to identify, defined in their pre-training.

Recent improvements in LLM text understanding opens up the possibility of using models for ‘intelligent’ text redaction according to specific user prompts and the broader context of the passages under review. This functionality is still very nascent in the Redaction app, however the basic ability to add custom labels to redaction tasks with local/cloud (AWS) LLMs has been added. From my experiments, I found that a local LLM model of moderate size (~30GB) can perform quite well at identifying PII in open text, and gives the ability to add custom entities to the analysis. In this example I will use a 4-bit quantised Gemma 3 27B model, which should fit within a consumer GPU (approx 20-24GB VRAM needed).

The example for this is ‘Example LLM PII detection’ on the Redaction app VLM Hugging Face space, and this will analyse the emails from this simple document. If you look at step 3, you will see that ‘Local transformers LLM’ is now the PII identification method, and a custom prompt has been added to the box below:

‘Redact Lauren’s name, email addresses, and phone numbers with the label LAUREN. Redact university names with the label UNIVERSITY.’.

The results from the first email in the document are below.

The prompt and response for the text above can be found here, and here.

The LLM follows the instructions, identifying only text directly related to Lauren and the university names. This is quite limited functionality compared to what a large language model could probably offer - in the near future I will do more experimentation with small, local LLMs to see what is possible.

Conclusion

In this post, we have seen how small local VLMs (from the Qwen 3 VL family), alone or alongside existing OCR tools, can be used as part of a redaction workflow to help extract text from ‘difficult’ documents and accurately locate text bounding boxes.

In these examples, Qwen 3 VL 8B Instruct was used alone or with PaddleOCR, and Gemma 3 27B was used for PII identification. Gemma 3 27B was quantised to 4-bit using bitsandbytes, resulting in a VRAM footprint of approximately 10-12GB for the VLM model and 20GB for the LLM model.

We have seen that for ‘easy’ documents (typed text), tesseract or PaddleOCR are generally sufficient. For ‘noisy’ documents, e.g. scanned documents with typed text, and small amounts of handwriting and signatures, the hybrid PaddleOCR + Qwen 3 VL approach is a good option. For difficult handwritten text, it is close between the hybrid and the the pure VLM approach as to the best quality approach, but I sided with the hybrid approach due to the increased reliability in identifying text locations, and including all text. This conclusion may change in the near future with the imminent release of the small Qwen 3.5 range of VL models, after which I will update this post.

Local VLMs such as Qwen 3 VL can also be used to add additional features to redaction workflows to identify photos of people’s faces and signatures in the document, and accurately locate them on the page.

Local LLMs of moderate size (~30GB) can be used to augment PII identification tasks, with the ability to identify custom entities in open text with some accuracy.

Overall, local VLMs have the potential to be used for redaction tasks, however, they are not quite there alone. Currently, for bounding box detection, they work better with the assistance of a ‘traditional’ OCR model such as PaddleOCR. With rapid advancements in AI, including local models, this of course could change in the very near future.